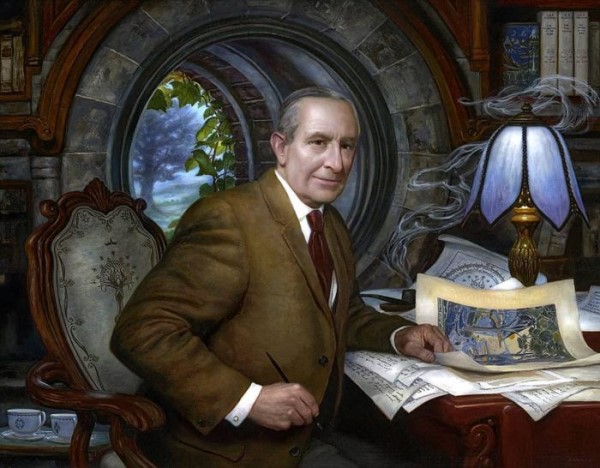

J. R. R. Tolkien belonged to a generation whose lives were irrevocably shattered by the First World War. In 1916, as a young Oxford graduate, he found himself at the epicentre of one of the bloodiest battles in human history — the Battle of the Somme.

Until 1914, Europeans had a romanticised view of war: cavalry, honour, quick victory. The reality turned out to be quite different. Industrial warfare turned people into expendable material.

In the trenches of France, Tolkien lost not only his illusions, but also his closest friends. He was a member of the Tea Club and Barrowian Society (TCBS), a group of four school friends who dreamed of changing the world through art. The war took two of them — Rob Gilson and Geoffrey Smith. The death of his friends was the turning point that changed Tolkien forever. He survived, having contracted trench fever, but returned home to a country where the old Victorian values had crumbled to dust.

The British Empire, belief in continuous progress and ‘civilised warfare’ had disappeared. It was in hospital, recovering from illness and grief, that Tolkien began to write the first drafts of what would later become The Silmarillion.

The impact of the war on the writer was tectonic. He did not write memoirs in the style of Remarque or Hemingway. He chose a different path. Why fantasy? Tolkien believed that reality after 1918 had become too painful for direct speech. The truth about the horror of war and the value of life is easier to convey through symbols.

He turned to archaic forms — legends, epics, myths — not as an escape into the past, but as an attempt to salvage the meanings that had been scattered. The symbolism in The Lord of the Rings is a direct response to the trauma of a generation:

- The dead marshes that Frodo and Sam walk through are an artistic description of the flooded craters at the Somme, where soldiers' bodies lay for years.

- The eagles do not arrive immediately. There are no easy solutions in life. Victory is achieved through exhaustion and walking through the darkness.

- Frodo does not return the same. This is one of the most honest descriptions of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) in literature. ‘How can you return to your old life when there is no longer room in your heart for the old world?’ is a question every veteran has asked themselves.

Language of Survival

Tolkien was a professional philologist. For him, languages did not exist without history, pain, and collective memory. He created Elvish languages (Quenya, Sindarin) knowing that words appear where there is experience.

For those who seek a deeper understanding, studying English through Tolkien's literature opens up incredible layers of meaning. Reading the original, you will notice how the style of speech changes: hobbits speak simple English, elves speak high, archaic English, and orcs use coarse slang.

This gives us a unique opportunity to understand the deeper meanings. Here is a small ‘glossary’ that will help you understand the meaning more deeply:

- Fellowship. In today's world, this word is often replaced by ‘team’ or ‘group.’ But for Tolkien, Fellowship is a sacred bond between people united by a common danger and goal. It is the same ‘brotherhood’ that we feel now in Ukraine.

- Shell shock (Concussion / PTSD). The term appeared during the First World War. Frodo's condition at the end of the book, his inability to find peace in peaceful Shire, is a classic description of post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Doom. In Old English, this word meant ‘judgement’ or ‘law,’ but in Tolkien's work, it takes on the connotation of inevitable fate. Mount Orodruin is called Mount Doom for a reason — it is the place of judgement.

Tolkien remains important reading in 2026 not because he once created the fantasy genre, but because he showed the mechanics of cultural survival in times of disaster. For Ukraine today, these are vitally important lessons:

- The dignity of the ‘little man.’ In Tolkien's work, the fate of the world is decided not by powerful kings or magicians, but by hobbits — ordinary people who simply wanted to live their lives but were forced to become heroes. It is a hymn to volunteers, doctors, and everyone who does their job despite their fears.

- Identity through language. Tolkien proved that destroyed nations preserve themselves through language and legends. As long as the word lives, the people live. Courses in English or any other language are not just about communication, they are about expanding one's cultural boundaries.

- Technology as a challenge. We live in the age of AI and drones. Tolkien warned that technology without morality (as in Saruman) leads to the destruction of the soul. Technology should serve life, not destroy it.

Tolkien's fantasy is not an escape from reality, but a way to comprehend it so that it does not break a person internally. It is a conversation about dignity instead of cynicism and about memory instead of oblivion.

The English-speaking community SARGOI always emphasises that language is a tool for understanding the world, not just a set of rules. Reading in the original and discussing books in English will not only help you improve your speaking skills, but also find like-minded people who understand the value of light in dark times. After all, as Sam Gamgee said, ‘There is good in the world, Mr. Frodo, and it is worth fighting for.’

A journey through time via the cult film Back to the Future

The Hobbit (1937)

The story that started it all. At first glance, it is a children's fairy tale about a journey in search of treasure. But in reality, it is a profound story about stepping outside your comfort zone. It teaches us that courage is not the absence of fear, but the ability to act despite it, and that even a ‘little person’ can change the world simply by stepping outside their own home.

The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955) This is no longer a fairy tale, but a heroic epic about the burden of responsibility. The book explores the corrupting nature of power and the saving power of the Fellowship. It is a chronicle of war, where victory is achieved not by force of arms, but by strength of spirit, self-sacrifice and mercy.

The Silmarillion (1977) This is a collection of myths about the creation of the world, the rise of the elves, and the first great wars against evil. The book explains why Tolkien's world is so profound.

For those who want to see Tolkien's manuscripts with their own eyes, we recommend visiting the British Library's online archives or watching documentary videos.